Nowadays, the city of Delft is synonymous with its earthenware that was produced in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Although it is still somewhat of a mystery why Delft became one of the main centers of faience production in the seventeenth century, it is interesting to explore the social, political and cultural climate in which these potteries were established and flourished.

The Republic of the United Provinces, as the Netherlands was officially known, was unquestionably a phenomenon amongst all the European monarchies. The Netherlands was a small, yet powerful state without a king, and during the second half of the seventeenth century the country was an economic and political force to be reckoned with.

The gap between the rich and poor was much smaller in the Netherlands than it was elsewhere

The country experienced a steady, uninterrupted growth in prosperity during the previous seventy years due to not only the accumulation of wealth, but also the technical and economic advantage that the Netherlands had over other European countries. This growth resulted in the highest average per capita income in Europe for a long period of time.

Further, the gap between the rich and poor was much smaller in the Netherlands than it was elsewhere. As a consequence, there was a very large, well-to-do middle class that could afford all sorts of luxuries, a unique phenomenon in Europe.1

Industrial city

At the onset of the Eighty Years’ War in the sixteenth century, the city of Delft was one of the largest and most powerful cities in Holland; it was the seat of the Royal Court and the political center of the new Republic. The trading cities of Holland greatly benefitted from the rapid economic growth from 1600 onwards due to both the development of trade and industry. However, trade never flourished in Delft, not even after the construction of the port of Delfshaven and the establishment of the chamber of the VOC (Dutch East India Company). The city primarily remained an industrial city.2

The growth of Delft in the seventeenth century was modest in size. In 1622, the city had 20,000 inhabitants and in 1680 there were approximately 22,000. Architectural growth lagged as well; only a few notable buildings were constructed after the major fire in the city of Delft in 1536.

The city’s other great ordeals, such as the dramatic explosion of the powder magazine in 1654, which wiped out a large number of houses in the city, hardly led to building plans for new residential areas, but mainly to the construction of large squares and gardens.3

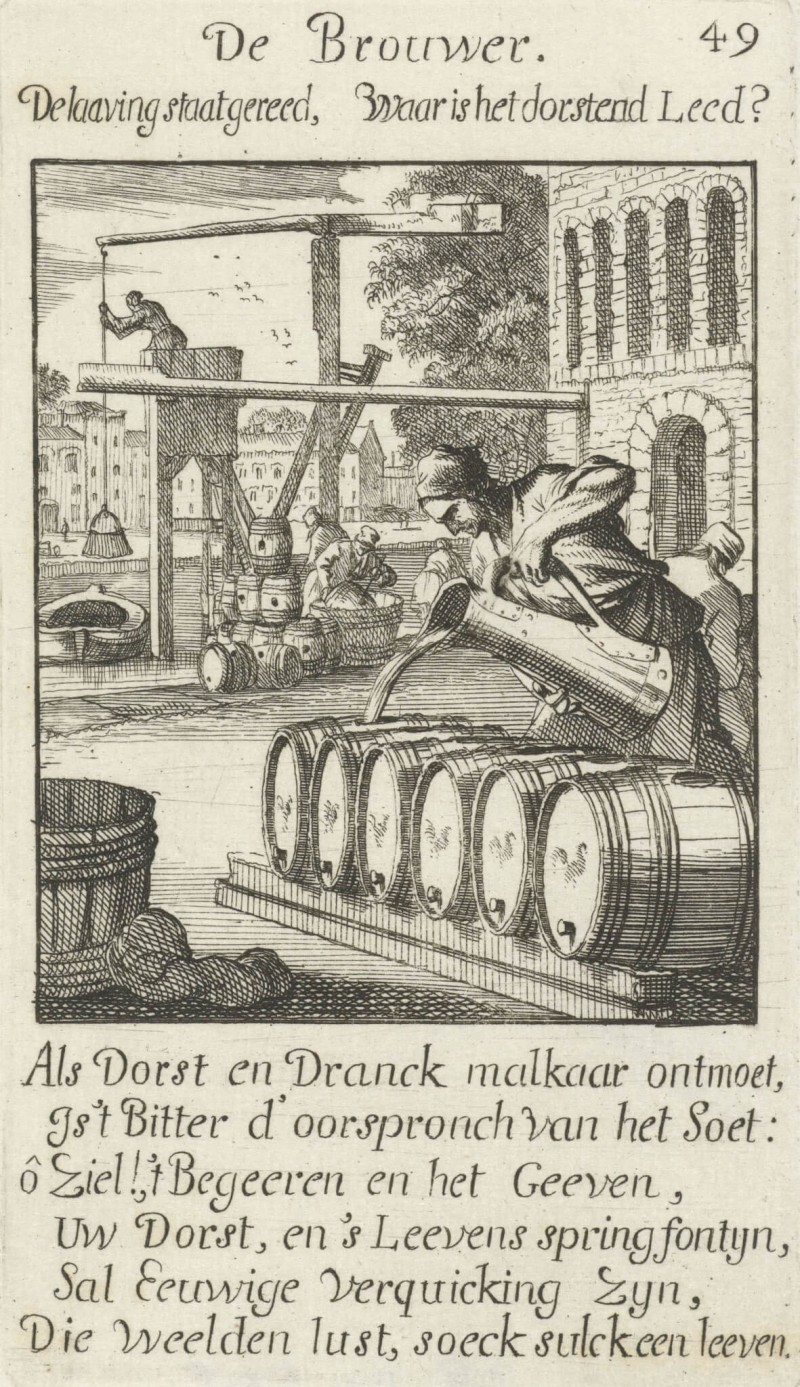

Breweries

Delft traditionally earned its wealth from the trade of grains and beer. During the sixteenth century, the brewing and textile industries were the most important trades and provided a large source of employment for the city of Delft. Despite their cultural and economic importance, these trades were problematic for Delft. The textile industry polluted the water, which consequently harmed the breweries as pure water was an indispensable ingredient for quality-made beer.

Already in the sixteenth century, this conflict of interest was settled in favor of the breweries. Nevertheless, the beer produced in Delft had suffered in quality and the industry declined towards the end of the sixteenth century.4 After the trade market ties were cut off from Flanders, Brabant and Northern France due to political circumstances, the emerging city of Rotterdam seized the market for the beer trade.5 Once the brewing industry yielded less in Delft, investors began to seek new ventures in land, government loans and shares of the VOC.

An important newcomer to the Delft economy was the pottery industry

To compensate for the loss of employment in the brewing industry, the city tried to attract textile entrepreneurs, especially among Flemish immigrants. However, this imported textile industry was only a moderate success. There were few Delft cloth traders who became rich. The industry was primarily intended to keep the poorest of the population off the street and to offer women and children a meager additional income.6 Only the carpet weaving industry was initially a more flourishing industry.7

Waterfront locations

The fact that Delft was at the heart of the Dutch Golden Age was mainly due to its position as a regional center. An important newcomer to the Delft economy was the pottery industry.

At the end of the sixteenth century several majolica potters settled in Delft and overtook the large abandoned brewing factories on the canals. The waterfront locations of these buildings proved to be convenient for the Delftware factories; the water was an important source of working the clay and for the transportation of raw and finished materials.

Delftware

With the production of Delftware, the earthenware industry grew enormously in the second half of the seventeenth century. In 1640, there were eleven factories with an average of fifteen painters and servants. In 1670, the number of factories grew to 28 and with approximately sixty employees per factory.8

Although the potters’ wealth and social influence was less than that of the former brewers,9 the pottery industry became the most important employer in the city of Delft.10 In the course of the eighteenth century, however, mutual competition became increasingly fierce and the sales market was also threatened. This resulted in the decrease of the number of factories; in 1750, twenty factories were still active and a mere eleven at the end of the century.11

Between 1680 and 1730, Delft lost almost a third of its population

Between the beginning of the Eighty Years’ War and the end of the eighteenth century, Delft changed from a relatively influential administrative center to a provincial town. Although Delft was the second largest city in the Netherlands in the mid-sixteenth century, after Amsterdam, several cities surpassed Delft in the seventeenth century. Between 1680 and 1730, Delft lost almost a third of its population, despite the success of the earthenware industry.12 The sharp decrease in population and eventual impoverishment was the result of rising food prices from 1770 onwards, and declining employment with the downfall of the earthenware industry.13

This article was previously published on the website of Aronson Delftware.

- 1J.D. van Dam, Delffse Porceleyne, Dutch Delftware 1620-1850, Zwolle/Amsterdam (Rijksmuseum), 2004 ,pp. 27-28

- 2M.S. van Aken-Fehmers, L.A. Schledorn, A.-G.Hesselink, T.M. Eliëns, Delfts aardewerk. Geschiedenis van een nationaal product, Volume I, Zwolle /The Hague (Gemeentemuseum) 1999, p. 37

- 3K. van der Wiel, 'Zicht op Delft in de 17de en 18de eeuw', in: De snijkunst verbeeld, 2002, p. 9

- 4Van Aken-Fehmers 1999 (note 1), p. 37

- 5Van der Wiel 2002 (note 3), p. 12

- 6Idem, pp. 12-13

- 7François Spierinck established a carpet weaving factory in Delft. The company of this renowned tapisier had several European courts among its clientele, but the proximity of other textile centers such as Leiden was a major obstacle to the development of a large meaningful textile industry. Van der Wiel 2002 (note 3), p. 12 and Van Aken-Fehmers 1991 (note 1), p. 37

- 8Van Aken-Fehmers 1991 (note 1), pp. 37-38

- 9Van der Wiel 2002 (note 3),p. 14

- 10Van Aken-Fehmers 1991 (note 1), p. 38

- 11Ibidem

- 12Van der Wiel 2002 (note 3), p. 11

- 13Idem, p. 31

Add new comment

Only logged in users can post comments

Log in or register to post comments