Dutch delftware evolved as an alternative to the porcelain from China which the Dutch East India Company (VOC) brought to the Dutch Republic in the early 17th century. The faience from Delft became an important export product and eventually evolved into an international icon of Dutch industry.

The first consignments of Oriental porcelain arrived in the Republic in the early 17th century. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) maintained a network that linked trading posts in Asia, where it bought Chinese porcelain and other goods. The porcelain was an instant success in the Netherlands, and soon became hugely popular among the elite.

Potters in several Dutch towns soon attempted to produce the best possible imitations. It was not possible to make real porcelain here, as the main ingredient, a special kind of clay , was not available. The copies were therefore based on a technique introduced by potters in Antwerp.

Glossy finish

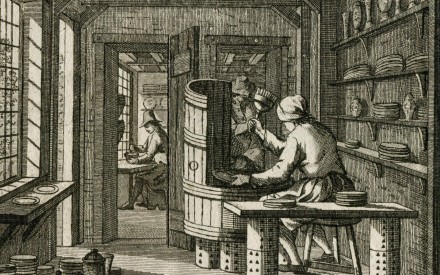

This technique involved adding tin to the glaze, which made it white. The technique was a very old one, which probably came to the north from the Middle East via Spain. Flemish potters who settled in Dutch towns like Haarlem, Amsterdam and Delft after the fall of Antwerp introduced it to the Netherlands. They made coarse domestic objects (plates, platters and bowls) that were tin-glazed and painted on one side.

Delft potters managed to make their pots thin, with a clean white surface and glossy finish

Delft potters using this technique managed to make a product with a thin body, a clean white surface and a glossy finish. The bright blue paintwork and shapes were copied from Chinese porcelain. The earthenware objects looked so good that they were referred to as Delft ‘porceleyn’.

Why Delft?

Although the Antwerp potters settled in several towns and cities in the Netherlands, including Haarlem, Gouda and Rotterdam, it was eventually those in Delft who improved their technique and made earthenware that looked like porcelain. This was able to happen in Delft due to a combination of economic circumstances.

Delft has a favourable geographical position on the Schie river, which connects it with the Dutch rivers area where some of the clay for the pottery was obtained, and with the major trading centres in the west of the country which accounted for a large proportion of the market for Dutch delftware. They, in turn, had links to the international market for Dutch delftware: England, France, Germany and the Southern Low Countries.

The potteries produced millions of objects a year and their products were sold all over the world

The pottery industry in Delft was in the hands of a small number of families who passed on their knowledge of the techniques to the next generation, and kept it secret. Furthermore, there was a branch (Chamber) of the VOC in Delft, which gave the residents of the town direct access to Chinese porcelain from Asia.

Dutch delftware became a cheaper alternative to real porcelain. It was in great demand and by 1625 there were already eight workshops and potteries making only Dutch delftware. At the height of the industry, around 1700, there were 34 workshops and potteries in the town. They produced millions of objects a year and their products were sold all over the world.

Competition and decline

But this golden age could not last forever. Cheaper products competed with Dutch delftware and became a growing threat. England and France were keen to boost their own economies and introduced a ban on imports, robbing Delft of a large market for its products. In the early 18th century, moreover, the first real European porcelain was produced in Germany. At the same time, porcelain from China grew steadily cheaper.

Real European porcelain was first made in Germany

Eventually it was English creamware that had the biggest impact on sales of Dutch delftware. The cream-coloured English earthenware was harder and cheaper than Delftware, so it was ideal for everyday use. Since around 90% of Dutch delftware was also for everyday use, creamware presented serious competition.

By the end of the 18th century only eleven potteries were still in operation in Delft. Of the original 17th-century factories, only De Porceleyne Fles still exists today.