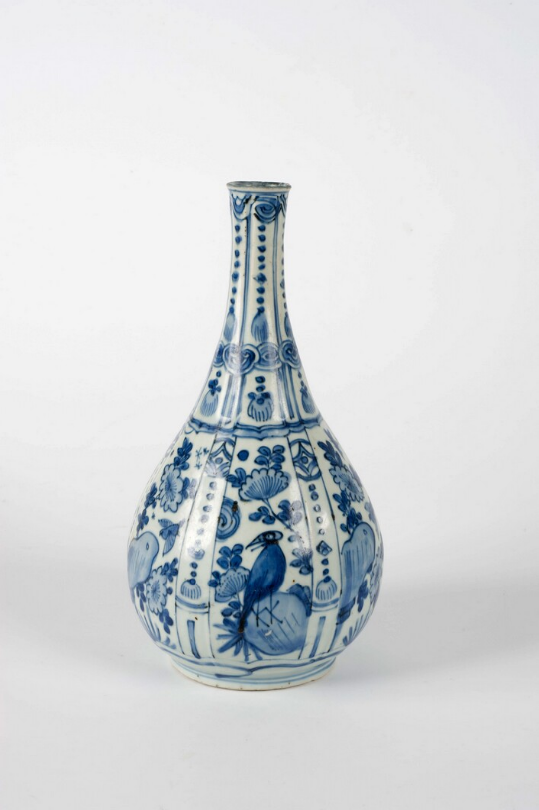

The Netherlands’ internationally renowned Dutch delftware is inextricably associated with oriental porcelain. This type of ceramic was brought to the trading centres of the Netherlands from the early 17th century onwards on the ships of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The production of Dutch delftware was the result of efforts by potters in Delft to imitate Chinese porcelain as closely as possible.

Porcelain has a hard, non-porous body, which is semi-transparent and white in colour. Its two main constituents are kaolin and petuntse (a type of granite containing the mineral feldspar).

When fired at a high temperature – around 1300-1500° C – the two constituents fuse together. During the second firing, the glaze likewise fuses completely with the body. The term ‘porcelain’ is said to derive from the Italian word porcella, a kind of seashell with a shiny, porcelain-like surface.

Meissen and Sèvres

Porcelain is the hardest type of ceramic and the method of producing it was not discovered in Europe until 1708. China had already been producing porcelain for a thousand years by then. Oriental export porcelain began to arrive in the Netherlands in the early seventeenth century. Various styles succeeded each other, with exotic names like Kraak porcelain (which is blue and white), Transitional and Kangxi porcelain, colourful Imari and Kakiemon, and polychrome porcelain.

Europe did not discover how to make porcelain until 1708

The first porcelain factory in Europe was established in 1710 in the German town of Meissen. It was under the protection of Augustus the Strong (1670-1733), Elector of Saxony. The porcelain made there – and at the factories established later in Vienna, Sèvres and elsewhere – was decorated in a range of colours, often combined with gilding. As with earthenware, the paintwork was often applied both under and over the glaze.

Earlier European attempts to imitate the coveted oriental porcelain led to the manufacture of a number of types of soft-paste (or pâte tendre) porcelain. That produced in Sèvres was the most successful. Soft-paste porcelain contains no kaolin (the essential ingredient of hard-paste porcelain) and is fired at a considerably lower temperature of only 1100° C.

Porceleynbakkers

In the Netherlands, good-quality porcelain was produced for short periods in the second half of the eighteenth century in Weesp, the Loosdrecht and Ouder- and Nieuwer Amstel. So-called ‘Hague’ porcelain was only decorated in The Hague, not made there, and although the Delft potters called themselves porceleynbakkers (‘porcelain producers’), true porcelain was never made in the town because the clay mixture did not contain kaolin. The difference between porcelain and Dutch delftware can be seen in areas of damage along the rims. On delftware, these reveal a yellow body beneath the white glaze, whereas true porcelain is white all the way through.

Add new comment

Only logged in users can post comments

Log in or register to post comments