The use of glaze containing the element tin is one of the most important features of Dutch delftware. Covering the entire object with this glaze, which becomes white on firing, allowed Delft potters to emulate Chinese porcelain as closely as possible. They learnt the technique from potters who left Antwerp after the Spanish invasion, though it had made a long journey to Europe before that.

From the Middle East to Spain

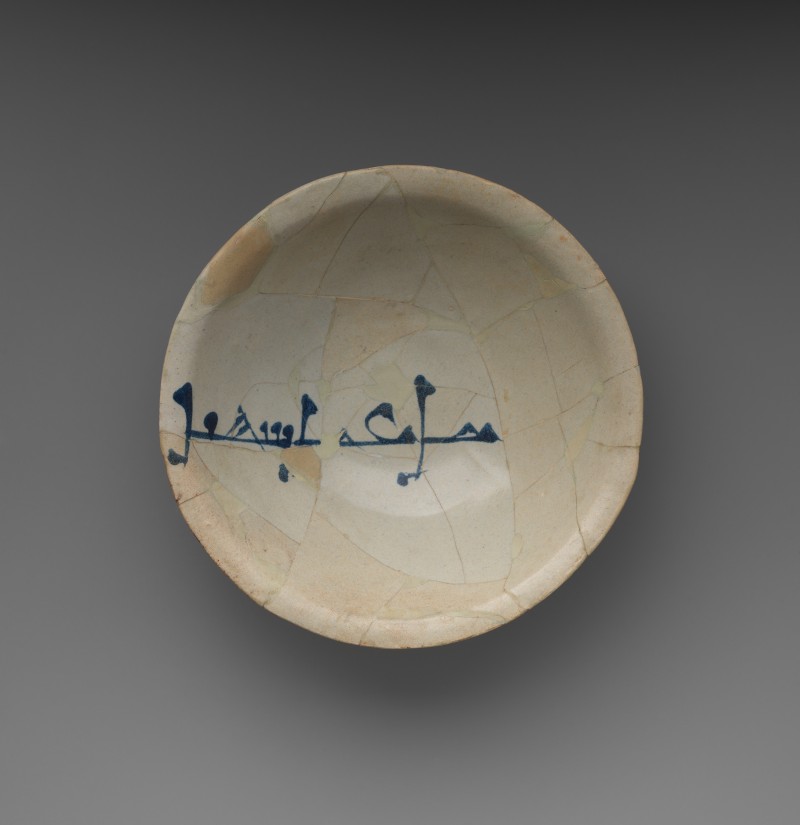

Tin glaze was probably first used in the Middle East in the 9th century (main image). Spaniards adopted the technique from Moorish potters who settled in Spain during the period of Islamic rule. From circa 1250 the earthenware was exported to Italy, via the island of Mallorca, and it therefore became known as maiolica. The Italian Cipriano Piccolpasso was the first to describe the use of tin glaze, around 1550.

Italian potters in search of new places to establish their trade moved to northern towns like Nevers and Antwerp. Potters in Antwerp mainly produced flatware – plates, platters etc. – for everyday use. It was glazed on the back using the cheaper but toxic and transparent lead glaze. But it had opaque white tin glaze on the front, often decorated using majolica colours like blue, yellow, green, manganese and rusty red.

The wares were traded via the island of Mallorca, and so became known as maiolica

These earthenware goods became known as majolica, with a j instead of an i. Majolica is fairly thick and has imprints of spurs, pegs placed between the objects in the kiln to stop them from fusing together during firing.

Challenge

After the fall of Antwerp in 1585 many majolica potters emigrated to Delft, Gouda, Haarlem and Rotterdam. The technique flourished in Haarlem, in particular, but in the late 16th century some majolica producers also established workshops in Delft. Dutch majolica was also known as plateel from the 17th century onwards. The potters in the Northern Low Countries produced both majolica and more refined tin-glazed earthenware (faience).

The majolica potters produced everyday ware for broad sections of the population, while only the wealthy bought porcelain from the East. It is not therefore likely that cheaper majolica experienced any threat from the Dutch East India Company’s porcelain trade. The porcelain is more likely to have been seen as a challenge to produce a similar kind of product.

Delft porceleyn

By introducing technical improvements to their production process, Delft majolica makers were able to produce more refined, luxury earthenware, which was known generally as 'Hollants' (Dutch), or in Delft, 'Delft porceleyn'. It is generally known as faience nowadays, to distinguish it from majolica. (The term faience, in common use internationally, refers to the town of Faenza, which from 1540 onwards was an important centre for the production of tin-glazed earthenware.)

In imitation of porcelain, Delft faience is covered on both sides with white tin glaze. Since it was relatively thin, and has blue-and-white decoration inspired by Chinese porcelain, Delftware became an attractive alternative to real porcelain.

Add new comment

Only logged in users can post comments

Log in or register to post comments