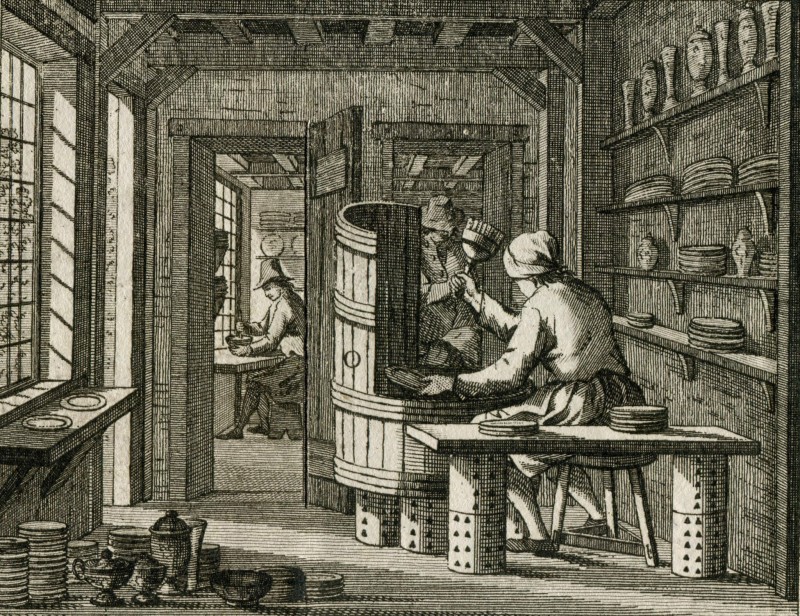

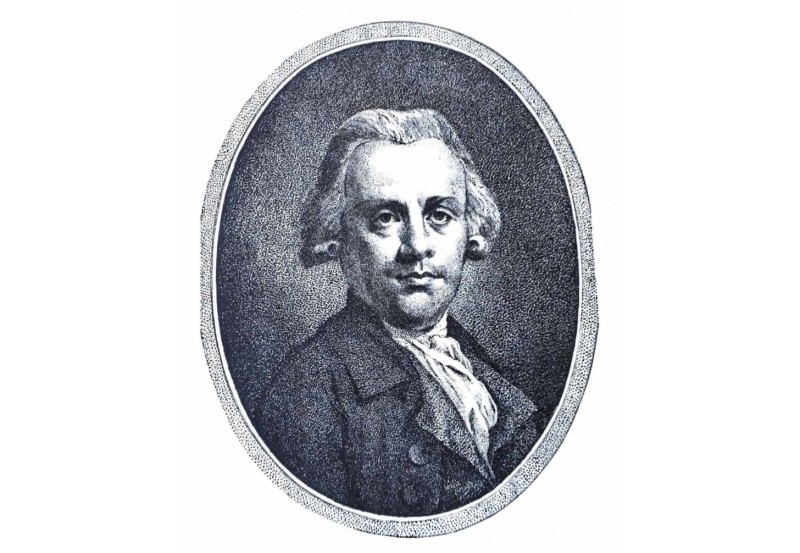

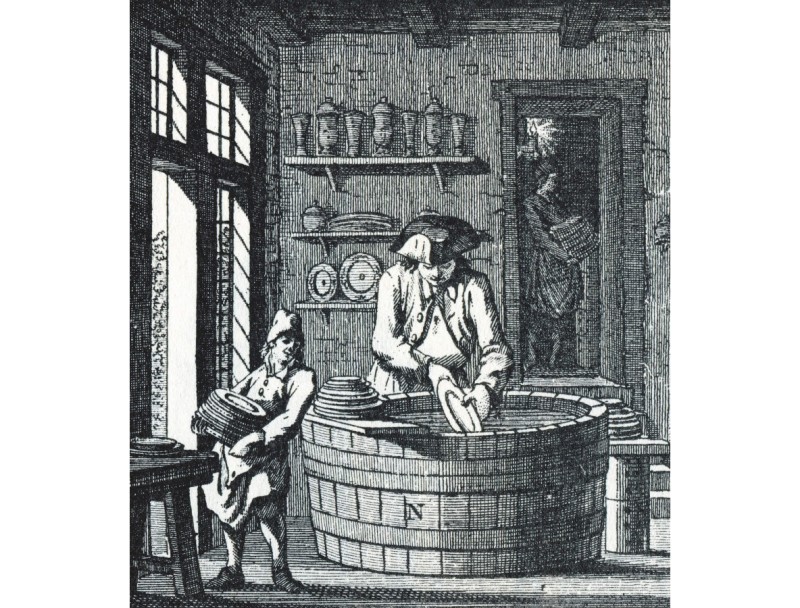

In the ceramics world, Gerrit Paape is renowned for his 1794 treatise De Plateelbakker of Delftsch Aardewerkmaaker (‘The Faience Potter or Maker of Delftware’). This publication, his sole work on Delftware, outlined many aspects of the eighteenth-century process of producing Delftware, making it an invaluable source of information about the industry. However, De Plateelbakker was only one of Paape’s many publications; he was also known for his patriotic treatises during the Batavian revolution at the end of the eighteenth century.

Paape was born into a large, poor family in the city of Delft on February 6, 1752. Since he could draw and paint well, his father placed him in a Delftware pottery in 1765, although the specific factory is unknown.

Paape successfully achieved the status of schildersknecht (painter’s servant) at the factory after ten years. In 1779, he was dismissed after a labor dispute and started a business painting fans and silhouettes. He also joined a circle of Delft poets, amateur artists and notables. In 1781, he was employed as a clerk at the Kamer van Charitate (“Chamber of Charity”), the local institution of poor relief. In 1782, he became one of the Patriots in the Batavian revolution.

Friesland

Gradually, Paape became a person of authority in Delft, whose opinions were heeded. After working at the Kamer van Charitate for five years, Paape became a journalist for the local paper, the Hollandsche Historische Courant, which was regarded as one of the most radical in the country. In 1788, he was ordered to leave the city by the magistrate of Delft for his patriotic attitude. Shortly after, he was exiled for life by the court of Holland on April 3, 1789 for lèse majesté. Paape first fled to Antwerp and then to Dunkirk, France in 1789.1

Although he was exiled for life, Paape then returned to the Netherlands

By 1794, Paape was appointed as secretary for General Herman Willem Daendels in Saint-Omer. Although he was exiled for life, Paape then returned to the Netherlands and briefly worked in Delft, Dordrecht and The Hague before accepting an honorable post in Leeuwarden, Friesland, in September 1796. There he was appointed to the Council of Justice, but without any legal qualifications.

Using a pseudonym, Paape resumed his journalistic work with the radical Friesche Courant, writing about revolutionary topics.2 The anti-French revolt of Kollum caused great strain in Friesland, and Daendels was called in to help. Paape, an anti-Orangist, squandered his position as an independent by running ahead of judicial procedures and verdicts. Paape was expelled, and in May 1797, he left for The Hague, disenchanted with The Batavian revolution.

The faience potter

Paape wrote De Plateelbakker during this turbulent political period. He dedicated the book to Lambertus Sanderus, the owner of De Klaauw (The Claw) factory from 1763 to 1806, since during his ownership high quality Delftware was produced and because Sanderus also was a patriot.3 The book was also dedicated to J. Reghter, who may have been a friend of Paape. Johannes (Jan) Reghter, as Paape mentions, was “zeer ervaren in het maken van fysische en andere instrumenten” (very experienced in making ‘physical’ and other instruments) and was known for his microscopes, planetariums, electrical devices and geometric instruments. Further, several illustrations in the book are drawn by Reghter.4

Other sources

Paape’s treatise on Delftware was not the first publication on this topic. Although not specifically on Delftware, the first treatise on the manufacture of tin-glazed earthenware was written by the Persian Abulquasim Abdallah ibn Ali, who was born in Kashan, Tabriz in 1301. This book describes how the clay was prepared for plates, jugs and tiles among other things.

Another well-known manuscript is Li Tre Libri dell’Arte del Vasaio, which was written between 1556 and 1559 by Cipriano Piccolpasso, born in Castel Durante in 1524. Piccolpasso mainly focused on majolica from Urbino, but also mentioned recipes that were used in other cities.5 With De Plateelbakker, Paape contributed a systematic treatise on the manufacture of Delftware, in which almost all facets were mentioned: from the beginning of the washing and kneading of the clay, the shaping of the objects, how they were put in the kiln and were fired, to the hairs that were used on the paint brush and the ingredients of the paints.

His fear of losing the national product or the industry may be the reason for his writing

Although the book provides great insights in the process of Delftware production, it is not always entirely clear. Names are usually explained, but some are still a mystery. For example, the meaning of the words ‘vetjes’ or ‘kloekkarel’, words that do not exist anymore in the Dutch language, has been lost over time. Further, Paape describes in detail the grand feu technique, but he does not mention the petit feu technique. Perhaps he left out this technique because it was rarely used in the last thirty years of the eighteenth century.

Paape wrote De Plateelbakker not only in a turbulent period of the country, but also during the downfall of the pottery industry in Delft. It is not clear why he, as a writer of mostly political texts, made the switch to the pottery industry. As he refers several times in the book to the decline of the factories, his fear of losing the national product or the industry may be the reason for his writing.

This article was previously published on the website of Aronson Delftware.

Add new comment

Only logged in users can post comments

Log in or register to post comments